Engineering Education

Publication Types:

Facilitating Engaging Journal Clubs in Online Upper-Level Undergraduate Courses

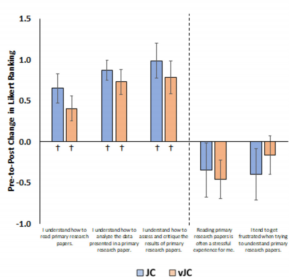

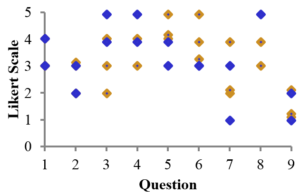

STEM curricula often prepare students with fundamental knowledge, allowing students to have strong backgrounds in technical concepts. However, upper-level students may lack the ability to critically analyze primary research articles, which is important for understanding the current state of the field. Journal clubs can be used within the classroom to facilitate discussion of recent work and teach students to critically analyze research and data. Traditional journal clubs (JCs) are conducted in face-to-face classrooms and consist of presentations and discussions. It is possible to adapt these techniques to form virtual Journal Clubs (vJCs) when courses are taught fully online; however, student engagement is often lacking and can lead to less knowledge gained in vJCs. In this article, we summarize several key teaching tips and best practices which we used to increase student engagement in vJCs. We found that vJCs, compared to JCs, equally increased student perceptions of their skills in reading, analyzing, and critiquing scientific literature and decreased their perceived levels of stress and frustration.

Exploring the relationship between student-perceived faculty encouragement, self-efficacy, and intent to persist in engineering programs

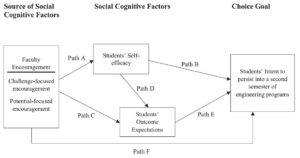

Copious research on Social Cognitive Career Theory has found student self–efficacy substantially related to persistence in engineering programs. The present exploratory study investigated the associations among faculty encouragement (a specific type of verbal persuasion in college context) and students’ self–efficacy, outcome expectations, and intent to persist in engineering majors using a sample of first-semester engineering students at a mid-sized public university. Analytical data were collected from 205 first-year engineering students in the fall semester at a mid-sized public four-year university in the United States. Results show that students’ perception of faculty encouragement can statistically significantly contribute to students’ self–efficacy and outcome expectations, supporting the hypothesis that student–perceived faculty encouragement was a source of self–efficacy and outcome expectations. Further, although students’ perception of faculty encouragement can influence students’ intent to persist, the effect was not directly transmitted; rather, it was found only through an indirect path via self–efficacy.

Using Arduinos to Transition a Bioinstrumentation Lab to Remote Learning

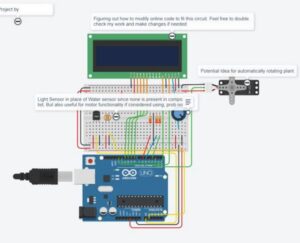

Bioinstrumentation is a required course in more than 75% of accredited BME programs. Like many other institutions, the bioinstrumentation lab at the University of Massachusetts Lowell (UMass Lowell) is a junior level course designed to provide the students with fundamental understanding of electrical circuits, circuit components, and bioinstrument design. The course meets weekly and the students progress through a series of labs where they build, test, and troubleshoot basic biosensor circuits. Example labs include building voltage dividers, active and passive filters, electrocardiogram (ECG), and electromyograph (EMG). Typically, these labs use a variety of equipments including function generators and oscilloscopes. UMass Lowell transitioned abruptly to remote learning during the spring semester of 2020 during which students were preparing to conduct their last lab (EMG) and begin their final semester project in groups of 2-3 students. Since the students no longer had access to the iWorx teaching kits and biosensors available in the lab, alternatives were explored which allowed students to still build and test circuits from home. It was determined that a cheap alternative is for each student to purchase the ELEGOO UNO Project Basic Starter Kit with Tutorial and UNO R3 Compatible with Arduino Integrated Development Environment (IDE). This paper describes our implementation appraoch.

Work in Progress: Design of a First-Year Rhetoric Course for Engineering Students

This Work in Progress paper describes an initiative to intervene at a curricular level, asking engineering students to consider writing as an essential and crucial element of being an engineer- and developing rhetorical awareness and writing skills. Educators and employers deem communication skills as critical for undergraduates (1), and ABET recognizes this by including “an ability to communicate effectively” as one of its stated student outcomes (2). However, this is an area that engineering students themselves perceive as the greatest gap in their undergraduate education (3). Furthermore, many engineering students undervalue the importance of writing skills and buy into the myth of engineers as ‘bad writers,’ believing themselves to be poor writers and communicators.

To achieve these goals, a committee composed of engineers from a variety of fields along with composition studies experts from the Undergraduate Rhetoric Program developed a curriculum designed to focus on introducing engineers to relevant genres and types of writing prominent in many kinds of engineering. The “Writing in Engineering Fields” course, designed to mirror the university’s first-year composition course, aims to inculcate these skills in a single semester. Writing assignments will include genres such as lab reports, abstracts, problem statements, technical instructions, and more “public”-oriented kinds of engineering writing. Also included are rhetorical reflections that ask students to consider the choices made in their own writing and to understand writing as a process in which they engage.

The course is structured so that students begin with an introduction to the Grand Challenges concepts, culminating in an assignment that asks students to analyze the written and rhetorical choices made across three texts that reflect a particular Grand Challenge concern, along with a rhetorical reflection. In addition, students will be introduced to the purposes and aims of writing as an engineer, as well as being introduced to the variety of writing genres engineers must master. The course continues into a second unit focused on writing that is primarily written by engineers to be read by other engineers, and includes discussion/study of genres such as problem statements, “state-of-art” reviews, and technical instructions, among others. This middle unit culminates in two different major assignments, a set of technical instructions and a ”state-of-art” review for the student’s chosen engineering field, each also having a rhetorical reflection attached. The final unit shifts to considering how engineers must be capable of writing towards non-engineering audiences as well as technically knowledgeable audiences, so this unit returns to asking students to consider the rhetorical choices required, culminating in a “remix” of an earlier assignment into a different, more public genre.

The course efficacy in achieving established goals will be assessed through a series of short surveys designed to evaluate students’ attitudes toward and perceptions of technical writing, along with an assessment of students’ proficiency in writing by a panel of faculty judges drawn from both the English and Engineering. The control group will consist of student volunteers taking the traditional first-year academic writing course and students who received no first-year writing instruction.

We believe that engineering students, some of whom may have tested out of the first-year composition requirements before their arrival, will find this course more relevant and engaging and will challenge the myth of engineers being poor or disinterested writers. In the longer term, professors in the students’ particular engineering disciplines will be better able to address specific, highly technical engineering genres, as their students will have been introduced to many of them, as well as to rhetorical and genre principles of writing in general.

Overcoming Difficulties in Research Statement Preparation for the Academic Job Search: Expansion of a Peer-Focused Professional Development Program

According to data from ASEE, women were awarded 23.1% of engineering doctoral degrees and held 15.7% of tenured/tenure-track faculty positions in 2015 versus 21.3% and 12.7% in 2009, respectively 1,2. This slight increase over six years is encouraging but also serves to highlight the continuing paucity of female engineering faculty. The causes are multifaceted, including a perceived lack of academic work-life balance, a diminished self-confidence after a PhD, and a lack of existing role models. To combat this problem, graduate students and faculty at a large public university started a multi-month professional development program designed to strengthen the preparation of prospective female faculty candidates. The main goal of the program is to address the gender gap in engineering academia by knowledge dissemination in a collaborative community. We strive to provide information to our participants through seminars and panel discussions, followed by peer review groups to share and review application materials. This is the third iteration of the program and significant changes have been made to further increase its efficacy. One major development is expanding the research statement segment of our programming. In this paper, we examine the effectiveness of this new structure and explore in further detail how to successfully break down the research statement writing process into tangible segments. Lastly, we explore the differences between the two structures and make preliminary comments on the success of our program’s expansion.

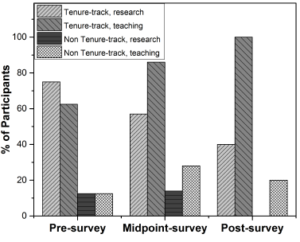

Keeping Current: An Update on the Structure and Evaluation of a Program for Graduate Women Interested in Engineering Academia

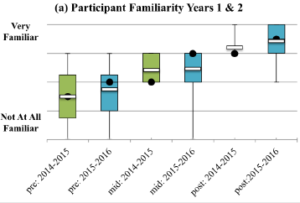

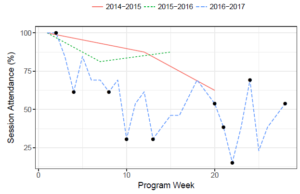

According to data from the ASEE, women were awarded 23.1% of doctoral degrees and held 15.7% of tenured/tenure-track faculty faculty positions in 2015 versus 21.3% and 12.7% in 2009, respectively [1, 2]. While promising, the “leaky pipeline” remains a persistent problem in the recruitment of underrepresented people into tenure track positions. To help overcome this barrier, we have created a program to improve the competitiveness of underrepresented applicants in the tenure-track faculty recruitment process at a large public university. The program activities are two-fold. First, seminars and panel discussions led by faculty representing different engineering disciplines cover a variety of topics related to the job search process. Second, peer review sessions over the course of several months allow students to develop their own application materials. Since its founding in 2014, the program has been evaluated by considering four elements: content, format, pace, and climate. The evaluations in the first two years were based on conducting pre-, mid-, and post-surveys as well as voluntary one-on-one exit interviews. For the program’s third year, we made significant changes based on past participant feedback. Specific topics were expanded to increase understanding and improve familiarity with the application process. The evaluation structure was revised to increase immediate feedback. In this paper, we discuss how the program has evolved over the three years as well as how our methods for program monitoring have been revised. By incorporating these changes, we aim to continue to prepare high quality female faculty candidates, thereby diminishing the gender gap in engineering academia.

"Blinded" Grading Rubrics for Bioengineering Lab Reports (Work in Progress)

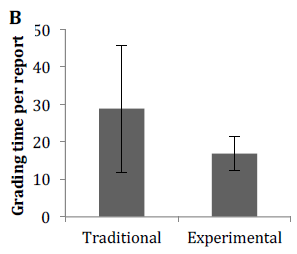

Large introductory laboratory courses are often assessed with a large number of written assignments requiring multiple graders. Consistency between graders for lab reports is an important issue for both students and instructors in order to maintain accuracy and fairness. This challenge is enhanced by the need for graduate student teaching assistants who often receive limited instruction on grading and have little or no experience grading technical writing documents. When presented with detailed rubrics, graders have preconceived notions about the definitions of “satisfactory” or “unsatisfactory” or similar descriptors and how these evaluations equate to a numeric grade. Even detailed rubrics that provide point designations for each item can result in inconsistent grading if graders have a preconceived notion of the overall score range that a report should fall into. To address these challenges, we propose using a “blinded” rubric where graders are encouraged to assess assignments only by qualitative descriptions on a rubric and not assign quantitative scores or points. Pre-assigned point designations for each statement on the rubric are then applied after the grader has evaluated all the reports. We hypothesize that this process will increase inter-grader consistency, increase grader confidence in evaluating work, and reduce overall grading time. We piloted this approach in a sophomore bioengineering laboratory course that employed three graduate student teaching assistants. Our preliminary results indicate that grader consistency increased using the blinded rubric system. Graders also reported greater confidence in their assessments. Further, graders reported spending less time grading assignments when they were asked only to select qualitative statements and not assign quantitative point values for their selection on the rubric. We are currently assessing student perceptions of this grading process, including fairness of the system and whether or not blinding graders to the initial point designations will encourage student-grader conversations to focus on the evaluations instead of points deducted.

Preparing Female Engineering Doctoral Students for the Academic Job Market Through a Training Program Inspired by Peer Review

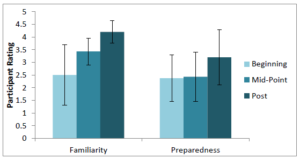

According to data collected by the National Science Foundation, women were conferred roughly 40% of doctoral degrees in STEM fields from 2002-2012, yet in 2010, women accounted for only 27% of tenure-track assistant professorships in engineering.1 The ‘leaky pipeline’ of women in STEM fields remains an ongoing discussion, with potential causes including student impressions of work-life balance in academia, a lack of role models in engineering, and decreased self-confidence following a doctoral degree. The Graduate Committee of the Society of Women Engineers (GradSWE) at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign has launched a program to specifically target the gender gap in engineering by improving the strength of faculty position applications from female doctoral students. The Illinois Female Engineers in Academic Training (iFEAT) is a multi-month program designed to strengthen the applications of female faculty candidates. Specifically, iFEAT provides informational resources for prospective faculty candidates through seminars and panel discussions, followed by peer review groups for students to share and review application materials. iFEAT aims to address several causes of the ‘leaky pipeline’ by increasing candidate confidence, introducing students to role models, and changing student perceptions of academic life. The program also aims to foster a supportive community through increased trainee interactions with faculty and peers. The peer review groups also provide opportunities for trainees to learn from each other, find mentors, and establish future relationships. Twelve female doctoral students were selected as iFEAT trainees based on their academic record, standing in their graduate program, and demonstrated commitment to academia. Surveys administered at the beginning, mid-point, and end of the program request trainees to self-report their aspirations and intentions for the academic job search, the progress of their application materials, and their confidence level in the application process. We seek to quantify any changes in the trainees’ goals, perceived preparation levels, and confidence levels throughout the program. As trainees progress through iFEAT and gain information about the application process, we will note shifts in perception of the most challenging and most important components of the application process. We will also monitor any changes in trainee career aspirations, including candidates’ preferred type(s) of institutions and academic positions, plans to conduct postdoctoral research, and anticipated application timeline. Trainees are also given the option to participate in a post-program interview, which is intended to uncover the reasoning behind any confirmations of or major changes in career plans and perceptions. Ultimately, we seek to track student outcomes from the program and uncover factors that may contribute to or prevent the ‘leaky pipeline’ of female engineers in academia.

A Program for Graduate Women in Engineering Pursuing Academic Careers (iFEAT: Illinois Female Engineers in Academia Training)

According to data collected by the National Science Foundation, women were conferred roughly 40% of doctoral degrees in STEM fields from 2002-2012, yet in 2010, women accounted for only 27% of tenure-track assistant professorships in engineering.1 While the gender gap in STEM fields remains an ongoing discussion,2-4 programs that provide resources and support for female engineering doctoral students interested in pursuing academic careers may help to address this gap. The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign regularly hosts seminars and afternoon-long workshops for doctoral students to learn about the academic job application process. Although these seminars and workshops are effective at disseminating information, they do little to encourage students to seriously consider, prepare for, and apply to faculty positions. To address the aforementioned issue, the Graduate Committee of the Society of Women Engineers (GradSWE) at Illinois developed the Illinois Female Engineers in Academia Training (iFEAT) program. iFEAT is a multi-month program with seminars and panel discussions, which are geared toward informing participants about the academic job application process, and independent peer review groups, which provide feedback on prepared application materials. Specific aims of iFEAT are for participants to demonstrate increased knowledge of the faculty position application process, to prepare tangible application materials, and to increase confidence in their application packages. To ensure program development, iFEAT will be evaluated primarily based on program (i)content, (ii) format, (iii) pace, and (iv) climate. The program structure was designed to encourage communication and camaraderie among participants and faculty. Approximately every 3 weeks,students will attend a seminar or faculty panel discussion. Between each of these major events,student peer review groups will share and review application materials. Seminars will provide information about applying for a faculty position, tailoring cover letters to specific job postings,understanding (or developing) a teaching philosophy, applying for funding (transforming a research statement into a funding proposal), and determining ideal recommenders (learning to cultivate relationships with potential recommenders). Panel discussions will widen students’perspectives toward developing a unique research statement, understanding the interview process, and negotiating a start-up package. Independent peer review groups will provide the primary form of feedback on application materials. Near the end of the program, students will‘submit’ their application packages to a different peer group that will act as a ‘search committee.’All members of the ‘search committee’ will read other applicants’ packages and provide anonymous feedback to the applicants. This process will help students better understand how search committees operate, as well as broaden the scope of their teaching and research statements. At the end of iFEAT, students will have a peer-reviewed draft of application materials, as well as access to professors who support the development and advancement of female faculty in engineering. Through iFEAT, we hope to increase the representation of women in academia, as well as improve the competitiveness of Illinois graduates seeking academic careers.